Chapter 1: Quest

Intelligent forces from Unseen Worlds help inform and direct the lives of people in this world. I don’t just believe this. I know it.

Over the millennia, people have given these forces different names, including God, gods, Ascended Masters, guardian angels, cherubim, seraphim, and spirit guides. Regardless of what they are called, they are as real as the book you are about to read.

I’m not a priest, pastor, rabbi, imam, guru or monk promoting a specific dogma. I come from a family with a history of alcoholism. My mother took her own life when I was still a very young man. I struggled for years with guilt, depression and my own alcohol addiction. Now I’m a former journalist reporting on the seemingly inexplicable events that turned me from a depressed and alcoholic skeptic into a content and sober spiritual seeker.

Rather than limit my vision to a finite existence in the material world, I now picture an infinite spiritual existence in a boundless and intelligent cosmos. Whether I’m writing a historical-spiritual novel or relating actual events, as I do in this book, my exploration of spiritual themes adds meaning to my life and strikes a deep chord in my soul.

Perhaps by reading my story, some devout materialists will question their certainties and at least entertain the possibility of spiritual realms. Perhaps some people struggling with a sense of hopelessness, as I once did, will consider embarking on a spiritual journey. For those already living spiritual lives, maybe reading of my experiences will deepen their beliefs.

I intend simply to provide evidence that Unseen Worlds are real. I hope this evidence will help you to advance along your own spiritual path and find greater meaning in life. I also hope it will help you to realize that there is no reason to fear death.

Chapter 2: Strange Presence

As I prepared for bed on the night of December 12, 1966, I sensed a presence in the room and felt a twinge of anxiety.

Strange, I thought.

At the time, I was an undergraduate exchange student spending a year in South Korea. I was staying for a couple of weeks at the home of the university president, an American missionary, so I was sleeping on a bed, not on the floor as I did when living in Korean households.

I checked the closet and under the bed for an intruder but found nothing. The search did not allay my concern, and my anxiety grew into full-fledged fear. Again I checked the closet and under the bed. I pulled back the curtains to look out the window. I repeated my survey four or five more times with the same result. Nothing. Yet my fear grew to the point of terror.

Even as a child, darkness did not frighten me, but on this night I was afraid to turn off the lights. I finally steeled myself to do so, climbed into bed, pulled the covers over my head and shook myself to sleep.

At 2 a.m. my aunt called from the United States to tell me my mother had hanged herself.

Many people have felt the presence of loved ones who have just passed away, perhaps you among them. A few tell of seeing and even conversing with them. Often the visitations provide solace to the living and an awareness that their dead relatives or friends are in a serene and loving place.

My mother, however, did not pass peacefully. I have early memories of a sane and loving mother, but for a number of years she suffered from depression that devolved into horrific mental illness. She had even been hospitalized with delusional paranoia and previously had tried to take her own life. After electroshock therapy she seemed greatly improved, so I did not expect to receive such stunning news.

What had I experienced that evening? Was my mother, who died on the other side of the world, trying to communicate with me? Did I empathically feel her fear and desperation as life left her while she hung from pipes in the utility room of our tiny suburban home? Did I experience the terror and confusion of a soul caught in a dark, in-between place, unable to make the transition into the light of the spirit world?

Correlation is not causation. Perhaps for some unknown reason unrelated to my mother’s death fear gripped me that night, but I doubt it.

At the time I looked skeptically at the notion that one’s consciousness could survive the death of the body. I was 19 years old. Death for me was a long way off and not something to think about. My concerns were with this world and what I could experience through the five senses, so I dismissed the fear I had felt as an inexplicable experience that proved nothing.

Yet, without my realizing it, a seed had been planted in my mind. Maybe, just maybe, Unseen Worlds are real.

Chapter 3: Korea

In 1966, trans-Pacific travel was far more expensive than it is today, so returning home for the funeral was not an option. I had been baptized Catholic, so on the day of the service I attended Mass at the Catholic cathedral in downtown Seoul and prayed for my mother.

Prayer on a regular basis, or even intermittently, was alien to me. In fact, I considered it so much hocus-pocus. I prayed that day out of respect, not a belief that my prayers would help my mother’s soul in the afterlife. Still, the gesture provided me with a bit of solace.

Back then, South Korea was a third-world country. Farmers still hauled produce on ox carts through the busy streets of Seoul. Most of the population subsisted on an income of less than a dollar a day. The thing that struck me most when I first arrived was the smell from open sewers, rotting garbage and animal waste in the streets.

But odor aside, I was having the adventure of my life. I grew up in Euclid, Ohio, a working-class suburb of Cleveland that didn’t even have a Chinese restaurant. Now I found myself immersed in an Asian culture very different from that of post-World War II America.

Chopsticks replaced knife and fork. Instead of cereal or eggs, breakfast consisted of rice and communal platters and bowls of fish and kimchi, a spicy and ubiquitous pickled cabbage dish. I committed my first cultural faux pas the day I arrived, when I walked into the house in which I would be staying with my shoes on. I never made that mistake again!

I studied Korean, but classes were held in English and attended by a few Korean students who wished to improve their foreign-language skills.

My favorite class was taught by professor Han Te Dong, who as a graduate student at Princeton had known Albert Einstein. We spent an entire semester translating the Tao Te Ching from Chinese to English to mathematics. The five-thousand-character book forms the basis of Taoism. To say I was out of my depth is an understatement, but I did pick up snippets of insight into the workings of the Eastern mind.

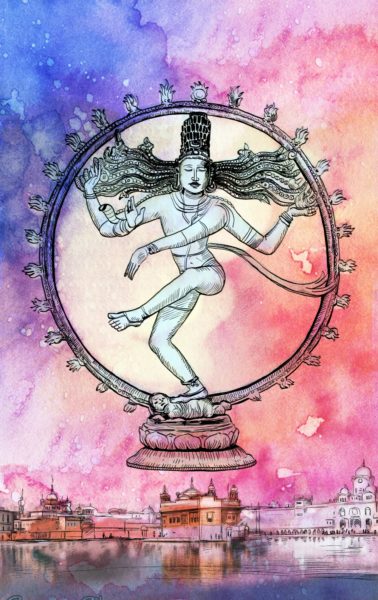

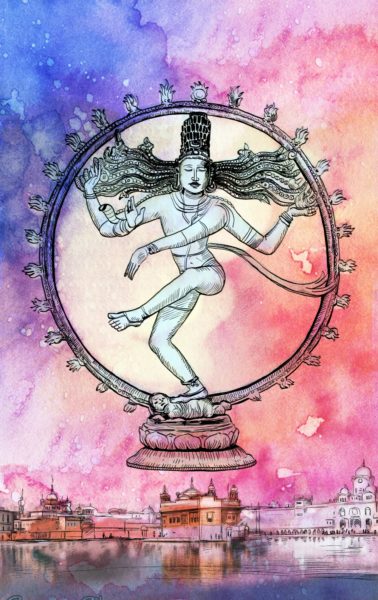

I augmented my study of Korean history and culture with journeys to historic sites, among them Haensa in south-central Korea. The “Temple of the Ocean Mudra” dates back twelve hundred years and houses more than eighty thousand fourteenth-century wooden printing blocks containing all of the Buddhist scriptures.

Isolated in the mountains, the shaven-headed monks and nuns brought spring water to the temple via a primitive but quite functional bamboo aqueduct. They fed my two friends and me simple fare, including a sumptuous soup made from moss gathered in the surrounding forest. Before we retired to a cramped sleeping cell, a nun lectured us on Buddhism. In the morning, before leaving, I bowed to the statue of the Buddha and left a small monetary offering — very small, reflecting my status as a poor student.

I had never felt such peace and serenity, but I was glad to get back on the road. I had a world to conquer, and a life of meditation and contemplation was not for me.